“Thripy” Mexican Mango Update

As we inch closer to the 2026 Mexican mango season, exporters tentatively aiming for a mid-January Ataulfo start, the orchards in Oaxaca and Chiapas have already begun telling their seasonal story. It’s a similar story about climate change and the unpredictability and complexity that comes with the shifting weather patterns . Orchard behavior continues to be capricious, and the mango farmer’s job grows increasingly active and expensive in the effort to achieve economically viable yields.

This update pulls together what I’m seeing, hearing, and tracking on the ground. Overall, things seem positive, but right now one word keeps surfacing in conversations with producers in the southern regions, particularly Oaxaca, which is the first region to begin: thrips.

I want to focus on thrips, even though I’m not convinced this is all bad news so much as important on the ground realities that needs greater awareness. For me, it feels like a lesson in transparency, and I take it on as another opportunity to learn more about mangoes myself and to share what I’m learning. As I often say, this is the kind of information no one really talks about, yet it’s exactly the kind we need to work through together. This type of news goes deeper than simple carton-count conversations and aligns closely with my own direct-trade ethos of connecting eaters and farmers through a truly connected supply chain. That connection only works if real information is shared — and, I’d argue, better absorbed across our industry.

Overall crop news remains generally positive, and I expect that to be reflected more clearly as we move week to week in future crop reports. For today, though, I want to focus specifically on thrips.

At this moment, the greatest pressure facing the Mexican mango industry continues to be pests and disease that come with erratic weather patterns. As I’ve written exhaustively over the last several years, climate change is the underlying driver. What’s different now is the speed at which conditions are shifting and the way orchards continue to be reliably unpredictable in their reactions. This makes for difficult growing conditions.

Thrips are currently a problem topic that everyone agrees on right now in both conventional and organic production in Oaxaca in particular.

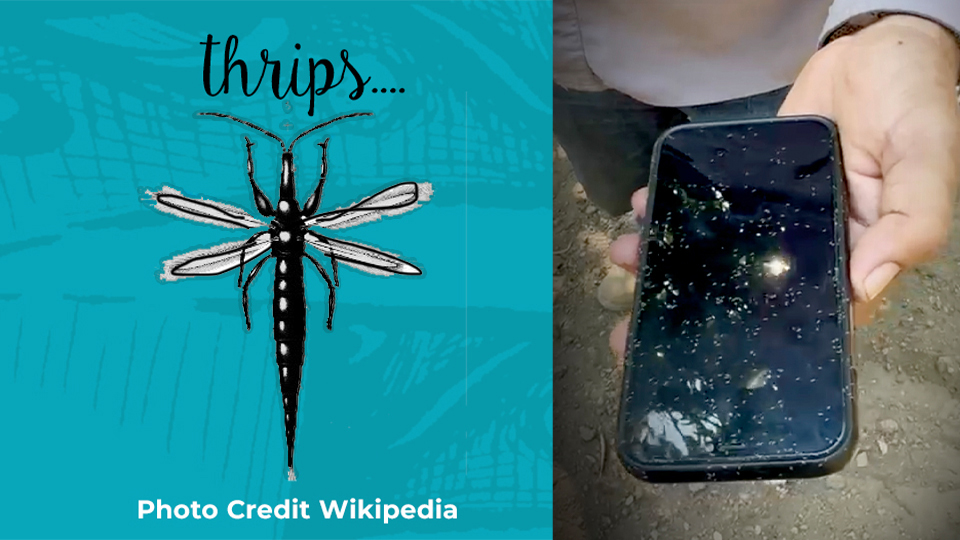

A thrip is a tiny, slender insect that feeds by piercing into plant tissue and sucking out cell contents. They are highly attracted to new growth, flowers, and very young fruit, which makes mango bloom time especially vulnerable. As mango panicles emerge and tender tissue appears, thrips move into orchards swiftly and most often unnoticed at first.

The bloom stage is incredibly attractive to thrips.

• panicles and flowers are soft and nutrient-dense

• tissue is fully exposed

• flowers remain vulnerable for an extended window

Adults fly in from surrounding vegetation, weeds, windbreaks, and neighboring crops. Females lay eggs directly into flower parts and panicle tissue, and larvae immediately begin feeding on pollen, petals, stamens, and ovary tissue. Under the right conditions, which many agree we are seeing, a full generation can complete in as little as 10–14 days, which is why populations can escalate so fast once they establish.

Many growers are linking this year’s thrips pressure to November rain and humidity, and that observation is not wrong — it just needs to be reframed. While month-by-month rainfall averages have not always show dramatic increases, which is why we can often have a debate about the “realness of climate change” there is growing evidence that southern Mexico, including Oaxaca, has experienced heavier and more disruptive rainfall events in recent years. Stronger and more frequent tropical systems have brought intense, concentrated rain that is not well captured by monthly data, yet has very real consequences on the ground for people and farmers.

These storms have driven catastrophic flooding, landslides, infrastructure damage, and loss of life in both rural and urban areas, underscoring that this is not an abstract climate discussion. For agriculture, the impact is immediate: saturated soils, explosive vegetative growth, prolonged humidity, and altered pest and disease cycles heading into bloom. Even when November rainfall totals appear “normal” on paper, the orchard reality tells a different story, as its doing now.

Heavy November rains increased vegetative growth in orchards and surrounding areas, expanding alternate host plants and shelter. Humidity supports survival and buildup in that vegetation. When rains taper off and bloom begins under warmer, calmer, drier windows, thrips migrate into mango panicles en masse. From the field perspective, it feels like “humidity brings thrips,” because the buildup happens earlier, even though the damage shows up later.

Why this matters is simple: bloom damage is yield damage, even if you can’t see it yet.

Thrips feeding during bloom causes problems long before fruit is visible. Panicles bronze and scar. Bronzing refers to the flowers and panicle stems taking on a dull coppery-brown or silvery cast instead of remaining green and healthy. This happens because thrips puncture the surface cells and suck out their contents, collapsing the tissue and disrupting normal color and function. Scarring is the physical injury left behind — roughened, corky, or dry patches on the panicle and flower parts where feeding occurred. Together, bronzing and scarring weaken the panicle, interfere with pollination, and often lead to flower drop or poor fruit set long before fruit is visible.

Flowers drop because thrips feeding weakens the flower tissue and disrupts normal development, causing blossoms to abort before pollination can occur. Even when flowers remain attached, pollination is often reduced because damaged stamens and pistils are less functional, and stressed flowers are less attractive to pollinators. When thrips feed on the ovary — the part of the flower that becomes the fruit — that damage can stop fruit formation entirely, leading to early fruit abortion. In cases where fruit does set, the injury occurred so early that the damaged tissue stretches as the mango grows, leaving visible scarring on the finished fruit. This is why heavy thrips pressure during bloom shows up weeks later as low fruit set and compromised quality down the road.

In terms of management, growers consistently stress that foundation work matters most.

- aggressive weed control before bloom to remove alternate hosts

• pruning for airflow and light to reduce warm, stagnant microclimates

• managing dust, which favors thrips outbreaks

Monitoring and timing are equally critical. Scouting begins as soon as panicles emerge. Shaking panicles over white paper (or cell phones these days!) to detect adults and larvae remains one of the most effective early-detection tools.

On the organic side, there are real limitations — and they are intentional. Organic growers do not use the conventional chemical toolbox many orchards are relying on right now. They work within more disciplined boundaries that prioritize long-term orchard and soil health over short-term suppression. When thrips pressure is high during bloom, those boundaries matter. Organic management depends on precision: timing, cultural controls (changing orchards conditions), early intervention, and a very small set of allowed materials. Rotation of resources is critical, thrips control only works when different methods are alternated over time and applications fully reach the flowers and panicles.

Spinosad is one of those limited tools — a biologically derived insecticide permitted under NOP certified organic production — but it is not a cure-all. Timing, restraint, and protecting pollinators all matter. The fact that growers are having to lean carefully on such a narrow toolbox right now speaks to how intense the pressure already is in the orchards.

According to a former phytosanitary coordinator for Mexican export programs, biological control remains one of the most important long-term strategies. He emphasized the role of beneficial predators, particularly Chrysoperla carnea, the green lacewing. Adults feed on nectar, pollen, and honeydew — the sticky residue left behind by sap-sucking insects like aphids and thrips. The larvae are the aggressive predators of the thrips as well as other small insects. He emphasized that lacewings are among the most important biological control insects in orchards, particularly when thrips pressure is addressed early.

Compounding all of this is disease pressure tied to these changing weather patterns is anthracnose, which many growers are now continuously having to combat in the south. There are organic compounds available for managing it, but this comes at significant cost. All of this additional work — increased applications, more labor, more monitoring — is driven by weather patterns farmers cannot control and is directly tied to lower, more unpredictable yields and reduced quality. At the same time, farmers are absorbing these rising costs while the market continues to push back relentlessly on price, even as costs increase across the entire supply chain.

It is still too early to see how all of this will ultimately play out. Fruit must bloom, set, and begin to form before any real conclusions can be drawn, and with each passing week the picture becomes a bit clearer — at least until the next challenge emerges. Growers are doing an extraordinary amount of work on the orchard side to hold quality together despite mounting pressures. These details and specifics matter, because they help clarify the real conditions farmers are operating under. We can argue endlessly over price, or we can be more transparent about reality and work toward pairing needs with solutions in a fair and just way. From my point of view, cooperative, direct-trade channels remain the strongest path forward, connecting the chain more honestly and benefiting everyone from orchard to table.

On the market side, Mexican Ataulfo season has officially begun for domestic consumption, with significant volumes moving throughout Mexico and in particular Mexico City. Some exporters are shipping conventional irradiated Ataulfos by air to overseas markets. For U.S. programs both organic and conventional, hot water bath packing houses are expected to begin opening shipping Ataulfos in mid-January. Tommy Atkins are expected to follow around the first week of February — all of this assuming things proceed as “normal,” a word that feels increasingly hard to define.

What is clear is this: thrips pressure is real, climate patterns are shifting faster than orchards can adapt, and growers are working harder than ever to hold yields and quality together. The season is approaching, but the outcome is still very much being written by what happens to the bloom.