SLOP & The Return to Authenticity

A year ago, most of us were pointing to global flavor trends, pricing pressure, or convenience as the forces shaping what came next. As people now reflect on 2025, many are understandably highlighting what moved, what sold, and what “worked” based on the realities as opposed to predictions. I can generally get behind the positive approach, but I also can’t help but focus on this one uncomfortable point as I reflect on the year behind me in my industry.

So, as I stand at the threshold of a new year and a new Mexican mango season, I want to place us directly in the pile of slop that dominated industry marketing and storytelling, something I feel strongly about—and examine both the damage and the antidote.

The good news is that authenticity—the antidote—is one of the trends projected to drive consumer desire in the coming year. It doesn’t require reinvention, but it does require fairness, greater transparency, more truth, and more actual work. It asks us to think beyond cases sold and engage with the real complexity of sustainability and long-term success. It may not be easy or comfortable, and it may not be for everyone—but it should be.

Merriam-Webster naming “slop” as the word of the 2025 year is a signal. Slop—mass-produced, low-quality content that offers little value has become a defining feature of how entire industries communicate—including our produce industry.

When the term entered the cultural conversation, it was framed largely as a critique of AI-generated content. But that framing has another important point less visible, AI did not create slop — it amplified it. Slop existed long before these AI tools, all AI did was make it cheap, faster to produce, and now everywhere, including our industry.

The produce industry was already vulnerable to this acceleration. For decades, it has struggled with marketing fluency, often confusing symbolism for connection and mistaking words and pictures for substance. The deeper truth of farm-to-table—that farmers and eaters are the most important forces in the chain—was frequently displaced by logistics-centered narratives focused on trucks, warehouses, food safety and scale-based storytelling.

Slop is not accidental. It forms when decision-makers are insulated from growers and eaters, allowing claims to drift away from practice without consequence. In produce, this disconnection concentrates in the middle of the supply chain. Farmers and eaters are separated by layers of brokers, marketers, and intermediaries who often understand neither side deeply. When truth is filtered, softened, or selectively shared between those two points, abstraction fills the gap. And abstraction is where slop thrives—sometimes carelessly, sometimes intentionally as a way to retain power.

For decades, produce marketing has relied on vague, reassuring language—responsibly grown, sustainably sourced, eco-friendly—phrases that sound comforting but are deliberately unanchored. They ask for trust without offering clarity or accountability. The avocado industry’s ongoing lawsuits over greenwashing claims are a clear example of where this leads.

As supply chains scale, the issue is not scale itself. It is how easily scale can now be pushed faster without consequences being felt evenly across the chain. Old tactics—scaling on the backs of farmers, withholding information, retaining margins in the middle—didn’t disappear. Marketing tools can now be used to make every company look and feel good to consumers without any actual facts all in the name of prioritizing case movement rather than any real commodity education or supply chain system literacy, AI has become another tool being used to perpetuate the imbalance, even in the news media’s approach.

What gets lost faster now is connectedness— that when held together by truth and transparency is what actually makes supply chains resilient. This slop economy has been building in our industry for years, long before AI, and for me the greatest example and maybe I can be so bold to say the greatest accelerator, long before AI is what I call the fairtrade–organic betrayal. Or when large multinationals got certified as fairtrade, operating small, certified fairtrade plots that were and still are framed as “righteous,” while operating the majority of their business’ in the same destructive conventional systems that created fairtrade in the first place. Those limited plots were and still are used and amplified to represent of the whole. Narrow participation in the actual movement was always the algorithm to soften the reality of their much larger, extractive middle-layer systems designed, to move cases, accumulate power and capture the majority of the margins.

As these few selective points were amplified the broader reality stayed obscure. The result is not neutral. Farming communities absorb the damage. Prices stagnate, risks increase, and growers become locked into systems originally framed as supportive but reengineered to serve power in the middle. Consumers were used and farmers were abused.

Fairtrade models have failed to deliver living wages or broad structural change: high certification costs, bureaucratic layers, market distortions, and premium leakage mean much of the value never reaches small farmers. Not to mention that large farming operations owned by multi nationals are now a huge part of the mix.

These programs these days often coexist without organic production and are just “fairtrade”, which is indefensible given organic’s proven benefits to farmworker health, soil, and long-term farming community viability. Instead of challenging unequal structures, the system have evolved to largely accommodate them—benefiting large cooperatives, exporters, and retailers more than farmers, farming communities and individual producers. Outside of minor charitable gestures, usually after margins have already been stripped, little changes in farmers’ and farming communities’ daily lives take place. Look at Ecuador and bananas for a clear view of this. Our industry has been using slop as a middle-layer tactic long before websters shone the light on it.

Clarity and truth are expensive. They require time, research, coordination, and real expertise. Authenticity also requires fairness. Slop persists not because people are unintelligent, but because ambiguity has long been rewarded in the middle of the supply chain. That ambiguity protects existing power structures. When clarity is absent, accountability weakens. Power concentrates, and the status quo holds.

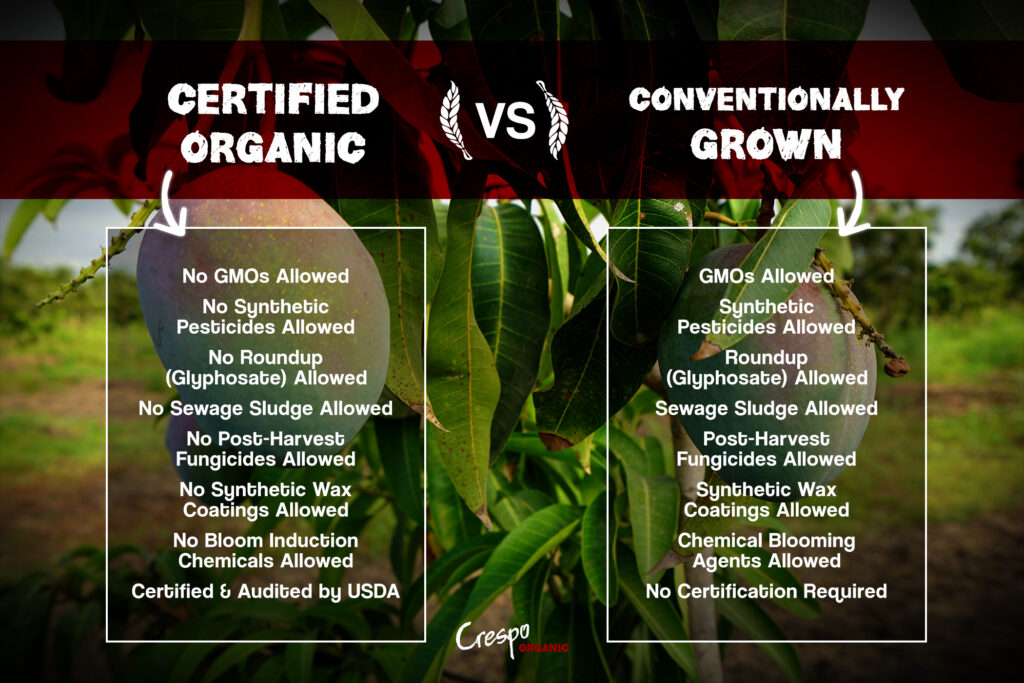

This is why I believe organic certification is still one of the most authentic things we can do in the produce industry and why I think it continues to trend and grow with such consumer confidence. Organic removes certain choices entirely. It replaces narrative with enforceable standards, audits, and third-party verification. It limits chemical exposure for farming communities, protects soil and water systems, and produces fruit that is healthier for the people eating it. The benefits are not abstract — they compound across the supply chain over time. Organic is imperfect, but it creates structural guardrails that reduce harm, increase transparency, and support long-term viability for both growers and consumers. Slop thrives in the gap between what is claimed and what is allowed. Organic narrows that gap by design.

What makes this moment in time different is not that consumers have suddenly became smarter. It is because our industry was sloppy and greedy. But I agree we are moving to a place where scale and repetition of all of our slop—accelerated by AI—has sharpened consumer detection. The vague claims they shoppers see repeated endlessly becomes so obvious as fluff, the same way most of the content AI creates. AI didn’t collapse the consumer trust; it exposed how thin it already was, especially in our industry. And there in lies the real opportunity for organic, direct-trade supply chains in the year ahead.

For those who are involved in authentic chains, consumers will notice. For those that wish to move from slop know that it is comparatively expensive — requiring real time, research, expertise, and coordination across the chain. Producing substance takes commitment, expertise and attention, and an underlying belief that farming communities’ success matters just as much as consumers receiving what they are promised. For those who choose not to engage in the produce slop: eco-friendly claims without context, people-first language without economics, conservation highlights detached from everyday practice. One initiative is elevated while chemical-dependent systems persist. Biodiversity is celebrated while insecticides remain in use. Water stewardship is claimed while synthetic fertilizers continue. This is your year. The year to focus on building

Authenticity shows up in how systems are built and enforced. It names tradeoffs instead of hiding them. It acknowledges limits. It shows process, not just outcome. It allows friction to be seen. It requires real conversations about quality, pricing, climate, labor, and risk. It introduces scrutiny. It forces coherence between how food is grown, handled, and described. It tells and shares the truth.

Crespo Organic is a relevant example here and despite my bias in it. It shows what authenticity looks like when it is operational. It shows how trust is built through consistency—how the mangoes are grown, how quality is protected, how information is shared, and how the fruit actually eats. When the system is real, storytelling becomes documentation. They do the work: organic farming, real transparency, and a supply chain built to keep growers and eaters connected in truth and reality rather than buffered by vague messaging. The trust the brand holds wasn’t created by content volume or polished social campaigns — it was earned, little by little, through consistency and partnerships over time.

It also shows how the work never ends and that it is a constant connecting of the links in the chain, sharing information, learning and growing. This is not about eliminating the middle. It is about restoring its function. When growers are supported and eaters receive what they are promised, the middle succeeds as connective tissue, not a bottleneck. The middle is crucial for the success.

My advice is simple: do the hard work your supply chain actually requires. Don’t take shortcuts or get sucked into believing the slop. Growers should be able to focus on growing. Eaters should receive food that delivers on flavor, quality, and trust. The chain should be built to move and evolve, each link fully reliant on the other and fully connected. Communicating. Strong supply chains endure because they are grounded in soil, flavor, farming communities, and truth. Orchard to table means exactly that.

[…] 2026 food trend predictions to my own musings on the antidote to the most negative food trend of SLOP & greenwashing — there is, as usual, a clear consensus around a core set of themes shaping how food will be […]